Only 0.01% of our seas are protected, and even the top conservation sites are up for grabs.

By George Monbiot, published on the Guardian’s website, 24th October 2014

A few days ago, I visited the Flamborough Head “no take zone”, one of the UK’s three areas in which commercial fishing is prohibited. Here marine life is allowed to proliferate, without being menaced by trawlers, scallop dredgers, drift nets, pots and all the other devices for rounding it up, some of which also rip the seabed to shreds. A reef of soft corals, mussels, razorfish and other species has begun to form, in which plaice and cod, crabs and lobsters can shelter, unmolested by exploitation. Fantastic, isn’t it?

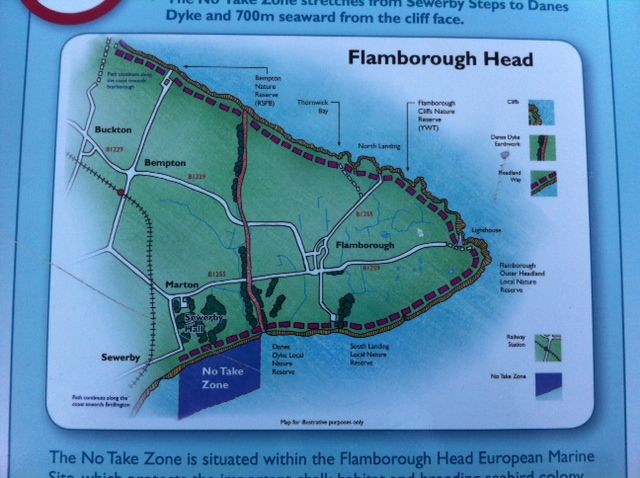

Well curb your enthusiasm. Here’s a map of the no take zone, from the display board above the beach. It’s the area in dark blue:

When I saw it, I thought of the scene from Blackadder Goes Forth, in which General Melchett explains to Lieutenant George how much ground the army has recaptured. Melchett shows him a three-dimensional representation of the land, on top of a table.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=09HTBiT3_lE

General Melchett: “Em, what is the actual scale of this map, Darling?”

Captain Darling: “Er, one to one sir.”

General Melchett: “Come again?”

Captain Darling: “The map is actually life-sized sir.”

General Melchett: “So the actual amount of land retaken is?”

Captain Darling (measures it): “Seventeen square feet sir.”

General Melchett: “Excellent. So you see young Blackadder didn’t die horribly in vain after all.”

This reserve, dear reader, is one-fifth of the total area of the United Kingdom’s no take zones. Yes, we have managed so far to protect five square kilometres from commercial extraction, out of the 48,000 square kilometres of our territorial waters.

In the US there’s a lively movement called Nature Needs Half. It campaigns for half the area of the land and sea to be set aside for the protection of wildlife: not very much to ask when you consider (as Alan Watson-Featherstone, founder of Trees for Life points out) that this means a single species gets 50%, while millions of others must make do with the rest. But how about Nature Needs 0.01%? How does that sound? Well that’s what our government believes the correct allocation should be.

And this, it seems, is how it’s going to stay. It’s not just that the government, which was supposed to have designated 127 marine conservation zones four years ago, has so far managed to leave 100 of them off the list, it’s also that the small number which have been approved are pretty well useless. They are little more than paper parks, lines on the map which make almost no difference to the life of the sea.

You might have imagined that a marine conservation zone would be a zone in which marine life was, well, conserved. That was certainly the expectation of the 500,000 people who signed the Marine Conservation Society’s petition calling for 30% of our seas to be designated strict marine reserves in 2009.

Doh! How naïve can you get? Conservation in a conservation zone? You must be out of your mind. Conservation zones, obviously, are places that fishing boats can continue to smash to pieces through beam trawling, scallop dredging and other weapons of mass destruction.

In fact even Special Areas of Conservation, which supposedly enjoy the strictest form of protection in the European Union, can still be treated as if the life they contain is worthless. Across most of these areas, trawling and dredging continue unhindered. But even where they have supposedly been stopped, the ban, it seems, can be overturned with a nod and a wink.

In August, the Duchy of Cornwall Oyster Farm applied to the government to annul a local law banning dredging in the Fal and Helford Special Area of Conservation in Cornwall. The byelaw had just been passed, to protect the fragile life of the seafloor. But the oyster farm, which hadn’t objected when the proposed law was put out for consultation, suddenly decided that it wanted to dredge for oysters there. Who owns the Duchy of Cornwall? Oh yes, that celebrated patron of conservation, Prince Charles.

The oyster farm leases the area in which it operates from the Duchy of Cornwall, and the income accrues to Prince Charles.

The Duchy has sought in the past to prevent public access to information about the oyster farm and its environmental impacts, but this was overturned in court, which ruled that the Duchy should be classed as a public authority, which should be open to public scrutiny. The judge also concluded, astonishingly, that he believed the Duchy of Cornwall had carried out no assessment of the farm’s environmental impacts.

For years the government has offered Prince Charles a veto over legislation that might affect the Duchy of Cornwall.

Without consulting anyone, the government instructed the Cornwall Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority to rescind the ban on dredging. Then, before the authority had a chance to respond, Westminster decided that this was such an urgent case that it couldn’t wait for any boring decisions by the local authority. It immediately issued an order rescinding the ban throughout Cornwall, on the grounds that the byelaw was “unnecessary, inadequate and disproportionate”.

The order was made on August 7th … and came into force the same day. The man responsible was the environment minister Rupert Ponsonby, or the 7th Baron de Mauley, who, like Prince Charles, owes his authority to tell us what to do entirely to heredity.

The Duchy says that while it is “clearly interested in understanding the impact of all new legislation which impacts on activity on the Helford and liaises with the appropriate authorities accordingly”, in this case it has “not been involved in changes to these Byelaws. Tenants are free to make their own representations …. dredging has been judged to be an acceptable activity on the Helford. On this basis the Byelaw is being amended.”

It looks to me like a royal stitch-up by a boot-licking baron of the kind you might have expected in the 14th Century, but that appears to sit comfortably with political life in the 21st. It could scarcely be a better illustration of the way in which the pre-democratic past continues to cast a shadow over democracy.

In her new treatise Conserving the Great Blue: overturning the dominant paradigm of the oceans, Deborah Wright proposes reversing our approach to marine conservation. Instead of assuming that everywhere can be exploited except those areas (generally tiny ones) designated as marine reserves, the assumption should be that everywhere is protected. If the fishing industry wants to exploit parts of the sea, it would first need to demonstrate that it can do so without lasting harm, in which case it would obtain a licence to go ahead. Destructive and damaging practices, instead of being the norm as they are today, would become criminal acts.

But for this to happen, we need to confront not only the fishing industry but also certain conservation groups.

That map of the pathetic no take zone occupies one of a number of display boards, which together comprise the Flamborough Storyboard project. Another provides a folksy eulogy to the local fishing industry. It’s entertaining, but there are two minor problems. The first is that it says not a word about the destructive impacts of the industry. In fact commercial fishing is portrayed as so benign and heroic that you feel it would be churlish even to raise the question. The second is that the boards were erected by the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust. Perhaps in future it should be known as the Yorkshire fishing industry’s marketing arm.

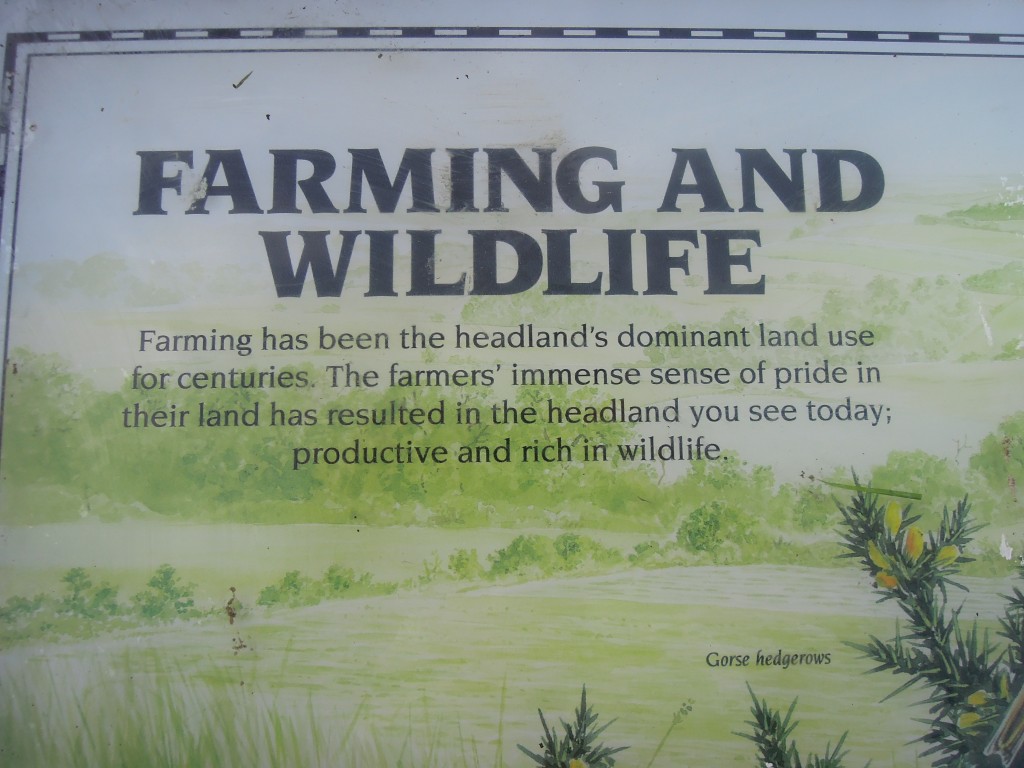

It gets worse. Here’s what another of its boards says about the local farming industry.

Behind it was the standard mixture of industrial monocultures – sheep pasture and arable fields – extending right up to the cliff path.

Just as the fishing industry is the principal cause of the loss of wildlife at sea, the farming industry is the principal cause of the loss of wildlife on land. Surely the role of the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust is to defend wildlife from these industries, rather than to produce misleading propaganda on their behalf?

Explaining these display boards, the trust’s website states that “scrub is controlled and the well-managed grassland provides an important habitat for insects alongside nesting sites for

skylark and meadow pipit”. But scrub tends to be far richer in bird species than meadows, and provides an essential resting and nesting place for the migrating birds – many of them much rarer and in greater need of help than skylarks and meadow pipits – that make Flamborough Head famous.

It’s a classic example of where conservation on land has gone wrong: the bodies charged with conserving our wildlife make decisions about which habitats to protect that look as if they are designed to accommodate not wildlife but powerful industrial interests. Farmers prefer sheep pasture to scrub, so wildlife trusts celebrate sheep pasture and wage war on scrub.

Now the same thing is happening at sea. Instead of campaigning to keep the fishing fleet out of large areas, to allow the proliferation of the magnificent life forms they could contain, the wildlife trust tells me it’s working “alongside the in-shore fishing industry to build wildlife-friendly fishing into the industry.”

Wildlife-friendly industrial fishing? It reminds me of the “green bombs” military scientists once claimed to be developing.

Sure, some forms of fishing are less damaging than others. That doesn’t make them wildlife-friendly. What is desperately needed – paradoxically for the fishing industry as well as wildlife – are large areas of seabed in which there is no fishing at all. Here fish, crustaceans and other species can mature and breed in peace. The “spillover effect”, as fish migrate out of large marine reserves, greatly boosts the overall catch levels. But so resistant have fishing interests been to the very idea of reserves that they would rather forgo this prospect than cede an inch of seabed to conservation. And so spineless are certain conservation groups, despite their huge memberships, that they would rather accommodate this attitude than confront it.

The result is that destruction is locked in, as the conservation policies that have done so little to help wildlife on land now spread to the sea. Instead of simply declaring large reserves off limits and letting wildlife do what it does best, the approach of governments and groups like the Wildlife Trusts is to identify “interest features” and design plans for their “management” (slight modifications of industrial practice) to keep them in “favourable condition” (which means only 80% trashed).

While there are many problems with this approach on land, at sea it’s even worse. There it’s much harder to assess the condition of the “interest features” being “managed”, harder to prevent the damaging industry from carrying on as before, and harder to assign responsibility when someone does the wrong kind of damage rather than the “right” kind.

When I contacted the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust, its chief executive told me: “We are not apologists for farming and fishing nor pushing out propaganda for them … The [display] board does not take a view on farming – it offers no support nor is it designed to campaign against the appalling state of British farming today. Likewise for fishing. We, of course, understand that fishing has devastated the North Sea’s wildlife – it is why YWT has built capacity to campaign on marine wildlife protection over the last five years. But again, regardless of our views on fishing, fishing has been part of the Flamborough community for thousands of years – it is part of the story of the people who live and work at Flamborough.”

So an organisation that believes British farming is in an appalling state and that fishing has devastated the North Sea’s wildlife is happy to tell the opposite story, sanitising and celebrating these industries, to the tens of thousands of people who visit Flamborough Head each year. When a conservation group censors itself on behalf of the interests it should be confronting, you get an inkling of how much trouble we’re in. And by the way, if stating that “the farmers’ immense sense of pride in their land has resulted in the headland you see today; productive and rich in wildlife” is not taking “a view on farming”, I’m a monkey’s uncle.

In 1776, Oliver Goldsmith described the arrival of a typical body of herring on the British coast. It was “divided into distinct columns, of five or six miles in length, and three or four broad; while the water before them curls up, as if forced out of its bed … the whole water seems alive; and is seen so black with them to a great distance, that the number seems inexhaustible.”

These shoals, he noted, were harried by swarms of dolphins, sharks … and pods of fin and sperm whales. In British waters, within sight of the shore.

They were also accompanied by great shoals of bluefin tuna, blue, porbeagle, thresher and mako sharks. On some parts of the seabed the eggs of the herring lay six feet deep.

Should that not be our ambition? To revive the astonishing abundance of the sea and its magnificent living wonders? Instead we fiddle with tiny variations on the theme of universal destruction. Except, that is, in the 0.01% of our waters that the government has so generously allocated to wildlife.

www.monbiot.com