The terrible legacy of European farm subsidies – and how we could use Brexit as an opportunity for something better

This is George Monbiot[1]‘s submission to the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee inquiry: The Future of the Natural Environment after the EU Referendum

- You have only to see satellite images of Britain and the rest of Europe to realise that there is something odd about this country. While average forest cover across Europe is 37%, in Britain it is 13%[2]. This contrast is explained by a remarkable quirk of distribution.

- In the rest of Europe, as you would expect, the lowlands are largely bare. This is where the land tends to be most fertile and the climate most suitable for agriculture. The uplands, where the soils are poorer and the climate harsher, are largely forested. As a result, the uplands of Europe are its great wildlife refuges, where large predators, wild herbivores and a wide range of species that cannot survive in an agricultural landscape persist.

- In Britain, strangely, the lowlands are largely bare and the uplands are even barer. This is not a natural condition. In Norway, at the same latitudes as northern Scotland, in similar climatic conditions, trees cover the high mountainsides[3]. The uplands of Britain would once have been largely forested. But, aside from plantations of exotic conifers, there are few trees in this country above 200m.

- Our bare hills are an artefact of three principal activities: sheep farming, deer stalking and grouse shooting. Sheep and deer selectively browse out tree seedlings, ensuring that existing forests cannot regenerate and trees cannot repopulate bare land.

- Sheep are a fully automated system for environmental destruction. Once they are released into the hills, no further human agency is required to prevent ecological recovery. While sheep densities throughout the British uplands tend to be well below economic viability, they are nevertheless too high to permit tree growth (which begins somewhere below 0.1 animals per hectare). Deer numbers on many Scottish estates are also maintained, in the absence of predators and through winter feeding, at levels well above the threshold.

- Grouse moors use rotational burning to produce a near-monoculture of low heather. This is of benefit to the small number of species that can thrive in such a habitat, but shuts out a much wider range of wildlife.

- Parts of the uplands harbour even less bird and insect life than the intensively farmed lowlands. There are ranges in Britain where you can walk all day and be lucky to see more than a few crows and the odd pipit. The 2013 State of Nature report found that while 60% of species across Britain have declined in the past 50 years, in the uplands the figure is 65%[4]. The contrast with the rest of Europe could not be greater: there the hills are alive[5], and not only with the sound of music.

- What explains this anomaly? The only answer that makes sense is the interaction between our distribution of land and the European subsidy regime.

- Without farm subsidies, there would be scarcely any hill farming in Europe: the activity is uneconomic almost everywhere and will remain so under all conceivable market conditions, as a result of poor soils and harsh climate. Anyone who wishes to farm there must rely on subsidies. Under the Common Agricultural Policy’s basic payment scheme, landowners are paid by the hectare. In the rest of Europe, most farms are not large enough to permit a living to be made only by harvesting public money. But Britain, on one estimate[6], has the second highest concentration of land ownership in the world, after Brazil. Here the landholdings are often big enough for owners and tenants to survive on public funds.

- Public money is used to keep land that would otherwise harbour rich habitats and wildlife bare. While I strongly believe that struggling local communities should be supported, the form this support takes is highly damaging to the wider public interest, as it relies on environmental destruction. It is likely to exacerbate flooding downstream and shuts down our principal opportunities for ecological restoration.

- Destruction is not an accidental outcome of the subsidy regime; it is a contractual requirement. You cannot claim subsidies for the land unless it is in “agricultural condition”. This does not mean that food needs to be produced there; merely that it must be bare. Land harbouring “permanent ineligible features” does not qualify. Permanent ineligible features are otherwise known as wildlife habitats: woodland, dense scrub, ponds, reedbeds, wide streams etc[7]. The CAP rules are a €55bn perverse incentive for habitat destruction.

- Across Europe, these rules have led to the pointless clearance of hundreds of thousands of hectares[8]. All the good things the EU has done for nature are more than counteracted by this bureaucratic perversity.

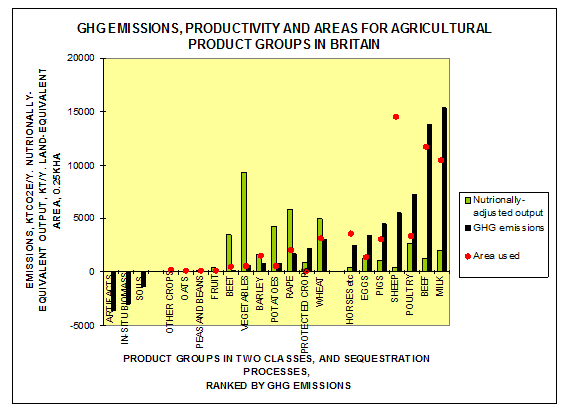

- For a small island, our use of land is remarkably profligate. Lamb accounts for less than 0.5% of our diet[9]. [Note added 5th January 2017: it now looks as if this figure applies to consumption in the home only – lamb eaten in restaurants will slightly raise this amount. I will update the estimate in a subsequent post]. Yet, according to figures produced by Zero Carbon Britain, sheep farming – as a result of the subsidy regime – occupies the same land area as all cereal crops put together[10] (see figure below).

Source: Zero Carbon Britain, 2013. http://peterharper.org/s/LANDUSEINZEROCARBONBRITAIN20302010-appendix.doc

- Hill farming has such a low yield that it might even be net-negative in terms of food production, as a result of the hydrological damage it causes to more productive farming downstream. It is hard to think of any human activity with a higher ratio of destruction to production. It has stripped the wildlife habitat from almost the entire upland area of England and Wales, while producing an insignificant amount of food (and wool with almost no market value).

- Where the hills have not been scoured by sheep or deer, grouse shoots have done the job instead. As well as the mass destruction of both predators and competitors (such as mountain hares), the burning and drainage of the moors causes wider habitat and species loss; results in the large-scale loss of nutrients and of carbon to the atmosphere[11]; and exacerbates floods downstream during high rainfall[12]. This too is subsidised by the taxpayer, as the government has chosen to classify grouse shoots as an agricultural activity.

- It seems contrary to reason that, while essential public services struggle for funds and austerity has been applied to almost every other aspect of public life, the subsidy for grouse moors has not only been sustained, but, under the last government, almost doubled[13].

- These seem to be indefensible uses of public money. If we are to spend money on subsidising industry, we should ensure that it delivers social goods, rather than social harm.

- A small proportion of Common Agricultural Policy funds is used for the purposes of greening. But this too is a perverse allocation. Pillar 2 schemes, such as Entry Level Stewardship and Higher Level Stewardship, counteract a small portion of the damage inflicted by Pillar 1 (the basic payment scheme). In other words, the two main elements of the Common Agricultural Policy are in conflict.

- But even Pillar 2 schemes arguably do more harm in this country than good. Though they are meant to be used to modify practices in favour of nature, the overall impact of Pillar 2 money is likely to be destructive. This is because, on unproductive land, Pillar 2 payments often sustain sheep farming that would otherwise cease. If ELS and HLS subsidies were no longer paid, the likely impact in the uplands would be a net gain for nature.

- Farm subsidies are highly regressive, drawing money from the pockets of all taxpayers and delivering it to some of the richest people not only in Britain but in the world. (You could see Britain’s foreign landowners as the world’s most successful benefit tourists). Because, in England, the payments are uncapped, some recipients receive millions of pounds a year.

- The remaining argument for their use is cultural. We are often told that they sustain a “cultural landscape”. But this raises some obvious questions. Whose culture? Whose landscape? Which history? The sheep monoculture of the uplands, where land use was once more diverse, owes as much to current market conditions, the current subsidy system and the recent era of headage payments as to deeper histories. Farming there has changed almost beyond recognition in the past few decades, obliterating centuries of cultural and landscape history.

- Claims to be preserving a cultural landscape tend to reflect the interests and practices of particular, dominant interest groups. This is not to say that there is nothing worth celebrating or defending. It is to suggest that the term cultural landscape should be used to open up a conversation, not close it down.

- I can think of two legitimate purposes for subsidies. The first is a rural hardship fund. But there is no obvious reason why farmers should be the main recipients. In England, they account for 0.3% of the general population and 1.4% of the rural population[14]. While many farmers suffer from low incomes, they tend to have greater capital, skills and opportunities than most other people with small earnings. There is no more reason to favour their profession with public charity than there is to provide a fund for distressed solicitors or plumbers. Money should be disbursed according to need, not occupation.

- The other purpose is an environmental protection fund, that pays exclusively for wildlife and habitats to be restored, floods to be prevented and children and adults to be brought back into contact with nature. I would have no objection to farmers living off such subsidies. In this case, we would be paying for public services, rather than public harm.

- I would not, however, favour an extension of certain current conservation practices. Just as there is something odd about the pattern of land use in this country, there has long been (though this is beginning to change) something odd about our conservation ethos. Whereas British conservationists campaign against the cutting, grazing and burning of natural habitats in other parts of the world, in this country some of them regard these practices as essential conservation tools. They appear to have lost the ability to distinguish between protection and destruction.

- The great majority of species require cover for their survival, to hide from predators, ambush prey and escape the extremes of temperature and humidity. But traditional conservation in this country has often focused on the tiny handful that can survive in open habitats, and has managed the land to favour those species, at the expense of the richer and more diverse ecosystems that would otherwise develop. A study in the Cairngorms found that wooded upland habitats are 11 times richer in nationally important species than grassland, and 13 times richer than moorland[15].

- Because the management of upland nature reserves has focused on protecting the species that have survived centuries of cutting, burning and grazing, rather than the wider diversity that could live here, conservation has favoured resilient species that tend to mature and breed quickly: known to ecologists as r-selected. It has tended to shut out those that mature and reproduce slowly (K-selected). This means, for example, most large carnivores and entire trophic groups, such as species that live on dead wood.

- We have been preserving the burnt-out shells of ecosystems, whose foodwebs are both narrow and shallow. There is no large area of land or sea in Britain free from the impact of intensive human management or exploitation. Universal land management, I believe, deprives us, and particularly our children, of experience. There is no comparison between immersing yourself in a place whose wonders are unscripted and unexpected, and visiting a reserve managed to within an inch of its life, in which you can expect to see little more than what is depicted on the noticeboard.

- This is not to say that such reserves lack all value. Some of them are loved in their current form by local people. Some protect species that are scarce elsewhere. But, as Sir John Lawton has proposed[16], if conservation is to be practised on a larger scale in this country, it should be done differently. There is a gathering appreciation that in some cases this means rewilding.

- I would define rewilding as the mass restoration of ecosystems and the re-establishment of missing species. In Britain it means allowing trees and other rich vegetation to return to some of the places in which farming is an unproductive land use. It means re-introducing animals and plants that cannot travel here unaided and allowing ecological processes – often driven by keystone species[17] – to resume, rather than constantly interrupting them with intensive management.

- Its purpose is to restore to the greatest extent possible ecology’s dynamic interactions. This means expanding the web of life both vertically and horizontally: increasing the number of trophic levels (top predators, middle predators, herbivores, plants, carrion and detritus feeders) and creating opportunities for the number and complexity of relationships at every level to rise.

- The rewilding of both land and sea could produce ecosystems here that are as profuse and captivating as those that people now travel halfway around the world to see. It has the potential to make magnificent wildlife accessible to everyone.

- It is also likely to ensure that our ecologies become more resilient to environmental change. Highly managed and simplified systems are often susceptable to profound disruption by invasive species, climate change and other threats. Diverse and dynamic systems, whose ecological niches are fully occupied, tend to be more robust[18].

- One challenge for rewilding is to demonstrate that it can support jobs and incomes for local people. In this respect, traditional industries tend to perform poorly. Despite the vast area it occupies and the subsidies it receives, farming in Wales contributes just over £400 million to the economy[19]. Walking produces over £500 million, and “wildlife-based activity” generates £1,900 million[20],[21]. The National Ecosystem Assessment shows that, across most of the uplands of Wales, switching from farming to multi-purpose woodland would produce an economic gain[22].

- Other traditional land uses offer similarly sparse employment. A study by the Scottish Gamekeepers’ Association found that, across the 780km² of deer-stalking estates it surveyed, just 112 people were in full-time-equivalent employment in the industry[23]. It also revealed that the income generated by stalking throughout Sutherland is just £1.6m, across 4,000km², despite expenditure of £4.7m.

- But can rewilding do better? More research is required. There are some excellent examples of wildlife restoration underpinning local economies. For example, colonisation by white-tailed sea eagles on the Isle of Mull has brought £5m a year into the island’s economy and supports 110 full-time jobs[24]. In the hills of southern Norway, the return of trees has been accompanied by a diversification and enrichment of the local economy[25]. The small income from farming is supplemented with eco-tourism, forest products, rough hunting, fishing, outdoor education, skiing and hiking. The question is how widely such success can be replicated. We don’t yet possess sufficient information to answer it.

- But what we can say is that rewilding costs less and therefore will lose less money than either hill farming or deer stalking. If owners and tenants were paid the same amount of public money to rewild as they are currently paid to farm, their net income would rise. If an area became more attractive to visitors as result of its richer wildlife and ecosystems, those who are not employed in farming are also likely to benefit. It could improve human welfare as well as environmental quality.

- Rewilding could be a lifeline to those who live and work in the uplands. How many people, post-Brexit, will be prepared to keep paying £3bn, roughly same as the NHS deficit, in farm subsidies whose current benefits are hard to discern? Taxpayers may be more inclined to part with this money when it produces such obvious public goods as functioning ecosystems and magnificent wildlife.

[1] I am an author and a freelance journalist, contracted to The Guardian. I was a co-founder of Rewilding Britain.

[2] http://www.forestry.gov.uk/website/forstats2014.nsf/lucontents/4b2add432342111280257361003d32c5

[3] http://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk/magazine/reforestation-in-norway-showing-what%E2%80%99s-possible-in-scotland-and-beyond

[4] http://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/stateofnature_tcm9-345839.pdf

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/21/waste-cash-leavers-in-out-land-subsidie

[6] See for example Kevin Cahill, 2002. Who Owns Britain and Ireland? Canongate.

[7] Rural Payments Agency, 2016. Basic Payments Scheme: rules for 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/546336/BPS_2016_scheme_rules_FINAL__DS_.pdf

[8] http://www.efncp.org/publications/books-reports-scientific-papers/

[9] Annual average lamb consumption per capita in the UK is 1.8 kg per year. 100g of lamb contains approximately 294kcal. So approximate annual average calorie intake from lamb is 5290kcal. Annual average total calorie intake per person in the UK is approximately 1.25m kcal. Therefore lamb provides roughly 0.4% of our calories. Imports and exports are almost exactly balanced.

[10] http://peterharper.org/s/UK-Food-and-Land-Use-Modelling-Spreadsheet-o2wx.xls

[11] Brown, L.E., Holden, J. & Palmer, S.M., 2014. Effects of Moorland Burning on the Ecohydrology of River basins. Key findings from the EMBER project. University of Leeds

http://www.wateratleeds.org/fileadmin/documents/water_at_leeds/Ember_report.pdf

[12] Joseph Holden et al 2015. Impact of prescribed burning on blanket peat hydrology. Water Resources Research DOI: 10.1002/2014WR016782

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/28/britain-plutocrats-landed-gentry-shotgun-owners

[14] https://www.monbiot.com/2012/06/08/captive-animals/

[15] P.Shaw and DBA Thompson, 2006. The nature of the Cairngorms: diversity in a changing environment. TSO: Edinburgh. 444 pp. ISBN: 9780114973261

[16] John Lawton, 2010. Making Space for Nature: A review of England’s Wildlife Sites and Ecological Network. DEFRA. http://archive.defra.gov.uk/environment/biodiversity/documents/201009space-for-nature.pdf

[17] A keystone species is one that has a larger impact on its environment than its numbers alone would suggest. Examples are beavers and wild boar.

[18] A well known example is the exclusion of invasive grey squirrels by pine martens: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-014-0632-7

[19] UK National Ecosystem Assessment, Chapter 20, http://uknea.unep-wcmc.org/Resources/tabid/82/Default.aspx.

[20] This covers conservation work, wildlife tourism, other jobs which would not exist were it not for wildlife, and academic and commercial research and consultancy.

[21] UK National Ecosystem Assessment, ibid.

[22] UK National Ecosystem Assessment, Chapter 22, Figure 22.2 Economic values that would arise from a change of land use from farming to multi-purpose woodland in Wales

(£ per year). http://uknea.unep-wcmc.org/Resources/tabid/82/Default.aspx.

[23] Peter Fraser, Angus MacKenzie, Donald MacKenzie, 2012. The economic importance of red deer to Scotland’s rural economy and the political threat now facing the country’s iconic species. Scottish Gamekeepers’ Association.

[24] BBC Scotland, 16th June 2011. Mull’s economy soars on wings of white-tailed eagles. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-13783555

[25] http://www.cifalscotland.org/docs/DuncanHalley_Woodlands&Norwegians.pdf