New research suggests there was no state of grace: for two million years humankind has been the natural world’s nemesis.

By George Monbiot, published in the Guardian 25th March 2014

You want to know who we are? Really? You think you do, but you will regret it. This article, if you have any love for the world, will inject you with a venom – a soul-scraping sadness – without an obvious antidote.

The Anthropocene, now a popular term among scientists, is the epoch in which we live: one dominated by human impacts on the living world. Most date it from the beginning of the industrial revolution. But it might have begun much earlier, with a killing spree that commenced two million years ago. What rose onto its hindlegs on the African savannahs was, from the outset, death: the destroyer of worlds.

Before Homo erectus, perhaps our first recognisably-human ancestor, emerged in Africa, the continent abounded with monsters. There were several species of elephants. There were sabretooths and false sabretooths, giant hyaenas and creatures like those released in The Hunger Games: amphicyonids, or bear dogs, vast predators with an enormous bite.

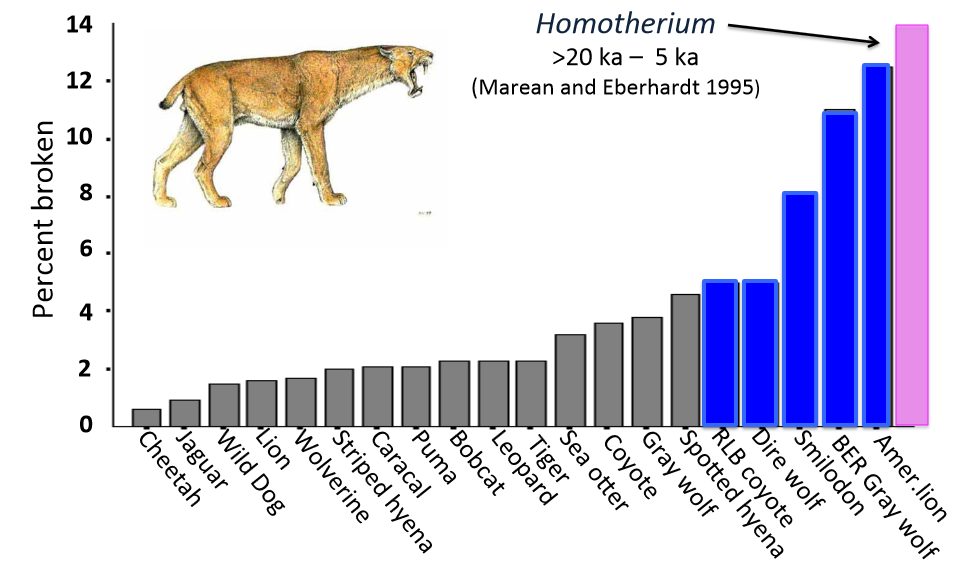

Professor Blaire van Valkenburgh has developed a means by which we could roughly determine how many of these animals there were(1). When there are few predators and plenty of prey, the predators eat only the best parts of the carcass. When competition is intense, they eat everything, including the bones. The more bones a carnivore eats, the more likely its teeth are to be worn or broken. The breakages in carnivores’ teeth were massively greater in the pre-human era(2).

Not only were there more species of predators, including species much larger than any found on earth today, but they appear to have been much more abundant – and desperate. We evolved in a terrible, wonderful world – that was no match for us.

Homo erectus possessed several traits that appear to have made it invincible: intelligence, cooperation; an ability to switch to almost any food when times were tough; and a throwing arm that allowed it to do something no other species has ever managed – to fight from a distance. (The increasing distance from which we fight is both a benchmark and a determinant of human history). It could have driven giant predators off their prey and harried monstrous herbivores to exhaustion and death.

As the paleontologists Lars Werdelin and Margaret Lewis show, the disappearance of much of the African megafauna appears to have coincided with the switch towards meat eating by human ancestors(3). The great extent and strange pattern of extinction (concentrated among huge, specialist animals at the top of the food chain) is not easy to explain by other means.

At the Oxford megafauna conference last week, I listened as many of the world’s leading scientists in this field mapped out a new understanding of the human impact on the planet(4). Almost everywhere we went, humankind erased a world of wonders, changing the way the biosphere functions. For example, modern humans arrived in Europe and Australia at about the same time – between 40 and 50,000 years ago – with similar consequences. In Europe, where animals had learnt to fear previous versions of the bipedal ape, the extinctions happened slowly. Within some 10 or 15,000 years, the continent had lost its straight-tusked elephants, forest rhinos, hippos, hyaenas and monstrous scimitar cats.

In Australia, where no hominim had set foot before modern humans arrived, the collapse was almost instant. The rhinoceros-sized wombat(5), the ten-foot kangaroo, the marsupial lion, the monitor lizard larger than a Nile crocodile(6), the giant marsupial tapir, the horned tortoise as big as a car(7) – all went, in ecological terms, overnight.

A few months ago, a well-publicised paper claimed that the great beasts of the Americas – mammoths and mastodons, giant ground sloths, lions and sabretooths, eight-foot beavers(8), a bird with a 26-foot wingspan(9) – could not have been exterminated by humans, because the fossil evidence for their extinction marginally pre-dates the evidence for human arrival(10).

I have never seen a paper demolished as elegantly and decisively as this was at last week’s conference. The archaeologist Todd Surovell demonstrated that the mismatch is just what you would expect if humans were responsible(11). Mass destruction is easy to detect in the fossil record: in one layer bones are everywhere, in the next they are nowhere. But people living at low densities with basic technologies leave almost no traces. With the human growth rates and kill rates you’d expect in the first pulse of settlement (about 14,000 years ago), the great beasts would have lasted only 1,000 years. His work suggests that the most reliable indicator of human arrival in the fossil record is a wave of large mammal extinctions.

These species were not just ornaments of the natural world. The new work presented at the conference suggests that they shaped the rest of the ecosystem. In Britain during the last interglacial period, elephants, rhinos and other great beasts maintained a mosaic of habitats: a mixture of closed canopy forest, open forest, glade and sward(12). In Australia, the sudden flush of vegetation that followed the loss of large herbivores caused stacks of leaf litter to build up, which became the rainforests’ pyre: fires (natural or manmade) soon transformed these lush places into dry forest and scrub(13).

In the Amazon and other regions, large herbivores moved nutrients from rich soils to poor ones, radically altering plant growth(14,15). One controversial paper suggests that the eradication of the monsters of the Americas caused such a sharp loss of atmospheric methane (generated in their guts) that it could have triggered the short ice age which began 12,800 years ago, called the Younger Dryas(16).

And still we have not stopped. Poaching has reduced the population of African forest elephants by 65% since 2002(17). The range of the Asian elephant – which once lived from Turkey to the coast of China – has contracted by 97%; the ranges of the Asian rhinos by over 99%(18). Elephants distribute the seeds of hundreds of rainforest tree species; without them these trees are functionally extinct(19,20).

Is this all we are? A diminutive monster that can leave no door closed, no hiding place intact, that is now doing to the great beasts of the sea what we did so long ago to the great beasts of the land? Or can we stop? Can we use our ingenuity, which for two million years has turned so inventively to destruction, to defy our evolutionary history?

www.monbiot.com

References:

1. eg Wendy J. Binder and Blaire Van Valkenburgh, 2010. A comparison of tooth wear and breakage in Rancho La Brea sabertooth cats and dire wolves across time. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724630903413016#.UzBUcM40uQk

2. http://www.eci.ox.ac.uk/news/events/2014/megafauna/valkenburgh.pdf

3. Lars Werdelin, 2013. King of Beasts. Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/magazine/sa/2013/11-01/

4. http://oxfordmegafauna.weebly.com/

5. Diprotodon.

6. Megalania.

7. http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/08/last-giant-land-turtle/

8. Castoroides ohioensis

9. The Argentine roc (Argentavis magnificens).

10. Matthew T. Boulanger and R. Lee Lyman, 2014. Northeastern North American Pleistocene megafauna chronologically overlapped minimally with Paleoindians. Quaternary Science Reviews 85, pp35-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.11.024

11. http://www.eci.ox.ac.uk/news/events/2014/megafauna/surovell.pdf

12. Christopher J. Sandom et al, 2014. High herbivore density associated with vegetation diversity in interglacial ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 111, no. 11, pp4162–4167. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1311014111

13. Susan Rule et al, 23rd March 2012. The Aftermath of Megafaunal Extinction: Ecosystem Transformation in Pleistocene Australia. Science Vol. 335, pp 1483-1486. doi: 10.1126/science.1214261. https://www.sciencemag.org/content/335/6075/1483.full

14. Christopher E. Doughty, AdamWolf and Yadvinder Malhi, 11 August 2013. The legacy of the Pleistocene megafauna extinctions on nutrient availability in Amazonia. Nature Geoscience vol. 6, pp761–764. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1895. http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v6/n9/full/ngeo1895.html

15. Adam Wolf, Christopher E. Doughty, Yadvinder Malhi, Lateral Diffusion of Nutrients by Mammalian Herbivores in Terrestrial Ecosystems. PLOS One, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071352. http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0071352

16. Felisa A. Smith, 2010. Methane emissions from extinct megafauna. Nature Geoscience 3, 374 – 375. doi:10.1038/ngeo877. http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v3/n6/full/ngeo877.html

17. Fiona Maisels, pers comm. This is an update of the figures published here: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0059469

18. http://www.eci.ox.ac.uk/news/events/2014/megafauna/campos.pdf

19. http://www.eci.ox.ac.uk/news/events/2014/megafauna/campos.pdf

20. http://www.eci.ox.ac.uk/news/events/2014/megafauna/galetti.pdf