National park authorities inflict mass destruction on wildlife and habitats, then call it conservation

By George Monbiot, published on the Guardian’s website, 14th January 2016

At one end of the country, conservation groups are doing all they can to stop the burning of moors. Challenging the grouse shooting estates, for example, the RSPB argues that “there is an urgent need to restore these landscapes by … bringing an end to burning.”

At the other end of the country, conservation groups are doing everything they can to ensure that moors are burnt.

Exmoor and Dartmoor, national parks covered by every possible conservation designation, are now in the middle of swaling season. Swaling is the term used in the West Country for burning the land. And the national park authorities, supposedly responsible for conserving and enhancing natural beauty and wildlife, oversee and assist the process.

Here’s how the Dartmoor authority justifies the practice:

“Dartmoor has been going up in flames in recent days – in an environmentally friendly way and much to the delight of various ground nesting birds like skylarks and grazing livestock.

“It’s all part of the age-old art of swaling – the notified controlled burning of overgrown heath land and clearing the ground of dead vegetation so that new growth can appear.

“This year swaling has been deemed more important than ever on the moors because fewer grazing animals have been released on the highland commons over recent years, resulting in the extra growth of plants such as gorse and bracken.”

Let’s take this step by step.

Environmentally friendly burning? Fossil fuel companies could take lessons in public relations from these people.

Why is it that practices we recognise as destructive when we see them elsewhere in the world are judged “environmentally friendly” here? When we see land being burnt in Indonesia or Brazil, do we call it conservation, or do we call it destruction? Because it damages soil and hydrology, incinerates wildlife and simplifies ecosystems, destruction is the correct term. Burning on Dartmoor has the same impacts. It’s about as environmentally friendly as tipping bleach into a river.

“Various ground nesting birds like skylarks” tends to mean, these days, just skylarks. Skylarks are used as the justification for every kind of destructive practice a land manager wants to inflict. This is because, unlike the great majority of wildlife, they can survive in open landscapes without cover, and they happen to be highly resilient to the forms of destruction we deplore when we see them encroaching on habitats in other countries: cutting, burning and grazing.

But “grazing livestock”: well that’s the nub of it. This burning has sod all to do with protecting the natural world and everything to do with extracting as much grazing from the land as possible. It continues in direct contradiction of the Sandford Principle, which is supposed to govern the management of national parks: that when there is a conflict between conservation and other uses, conservation should take priority.

As for “overgrown” heath land, “clearing the ground of dead vegetation” and “extra growth of plants such as gorse and bracken”, these are classic examples of the mortal fear of natural processes entertained by conservation bodies in this country.

An entirely treeless landscape, maintained this way by a savage regime of burning and grazing over many years, becomes “overgrown” the moment it starts to recover. The beginning of successional processes (“extra growth of plants such as gorse and bracken”) is regarded as a threat. We all know what happens next. Scrub grows and then, God help us, trees. Wildlife is returning: quick, fetch the matches!

The Exmoor National Park authority uses a similar justification:

“Exmoor National Park Authority is particularly keen to support swaling on Exmoor. Swaling maintains the character of the landscape by rejuvenating moorland plants, which in turn provides grazing for livestock and habitats for wildlife.”

Here’s the photo the park authority uses to illustrate the practice:

What do you see in the background? Miles and miles of bugger all, a treeless waste, kept in that state by a process the park is “particularly keen to support”.

This is not the only form of elective destruction in which Exmoor National Park engages. It employs other methods to ensure that trees don’t grow and rich habitats can’t return. The local sheep farmers don’t put their animals on the highest land, known as The Chains. So the park authority contracts a grazier on an annual basis to keep it mown.

I understand that in some places there is a difficult balance to be struck between the demands of tenants and commoners who graze their animals on the moor and the conservation of wildlife. I happen to believe that too much weight is given to sheep farming, and too little to wildlife. But where there are no tenants and no grazing, instead of using this as an opportunity for ecological restoration, the Exmoor authority is bringing in its own sheep to ensure that seedlings can’t grow and wildlife can’t recover. It’s utter madness.

I’ve made a short film for the BBC, broadcast yesterday, about these practices, in which I challenge the Exmoor park’s staff.

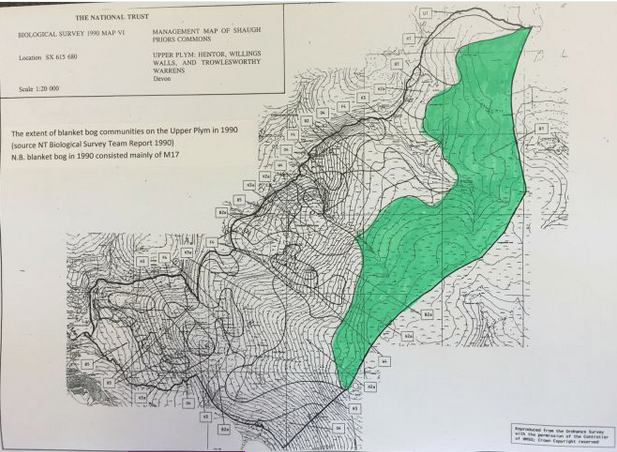

Even by the parks’ own criteria, swaling and grazing are causing an environmental disaster. Adrian Colston, the National Trust’s general manager on Dartmoor, has published a series of maps showing the astonishing deterioration over the past 25 years of the habitats the park claims to be protecting. Here is his map of good quality blanket bog in 1990:

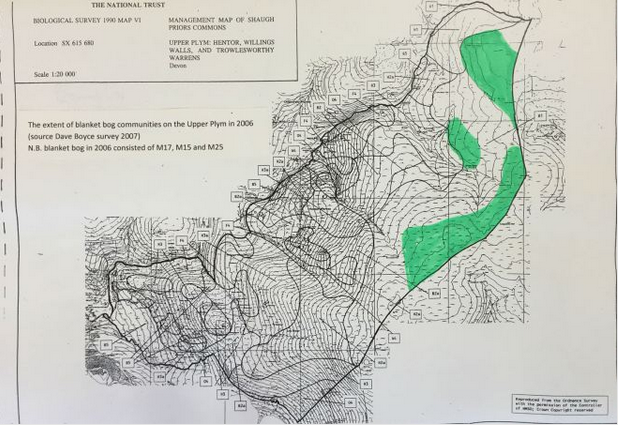

And here’s the extent of it in 2006:

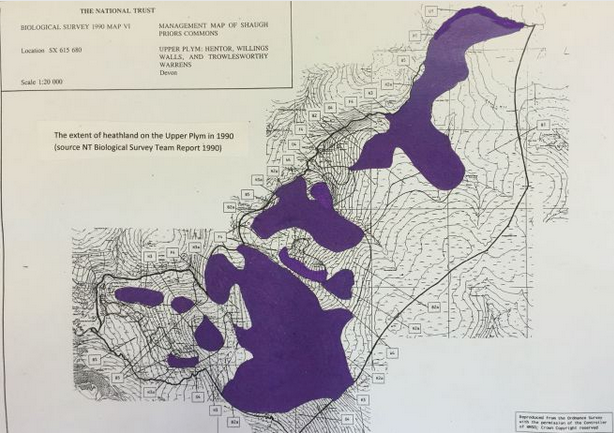

Here’s heathland in 1990:

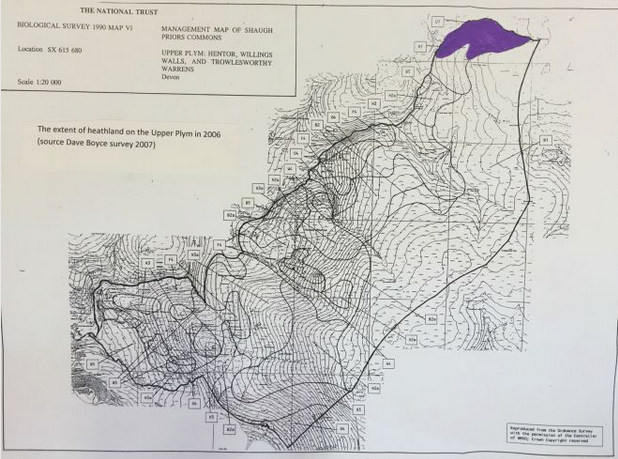

And in 2006:

As he reports, “These maps do not tell a happy tale. Our land is now in far worse condition than it was in 1990 as a result of overgrazing and burning (known as swaling on Dartmoor).”

The places in which we are invited to escape the impacts of humanity’s assaults on the natural world are being destroyed with the active collusion of the authorities charged with protecting them.

Not only have they failed to discharge their role as guardians of our natural wonders, but they also systematically mislead people about what they are doing, describing destructive practices as beneficial to the natural world. Since when did the duties of our national park authorities extend to greenwashing?

And that’s not the worst of it, as the criteria they use are highly questionable in the first place. Why, for example, do we see moorland as the desirable ecosystem on our hilltops, rather than more advanced successional states, such as woodland? Upland woods are vanishingly rare in Britain, but they harbour a far greater range of wildlife than moors do.

Because there are so few of them, comparative studies are scarce. But in the Cairngorms there is enough woodland to create a meaningful contrast. The results? Wooded habitats are 13 times richer in nationally important species than moorland*. There are 223 species on the massif which are found nowhere else in Britain. Of these, 100 are associated with woodland or trees. But just one – a fungus that lives on bilberry leaves – requires moorland for its survival.

So why is heather moorland, a highly impoverished habitat which results from repeated cutting and grazing, our conservation priority? When we see such degraded ecosystems elsewhere in the world, we recognise them for what they are: the products of deforestation.

In either case, both the Dartmoor and Exmoor national park authorities (in common with the bodies running most of Britain’s other national parks) are wide open to legal challenge under the European Habitats Directive, for failing to keep these supposed wildlife refuges in favourable conservation status. Such challenges require time and money. Does any conservation body have the nerve to take on the national parks?

In October (and fair play to them), I was invited to talk to the UK National Parks conference, on Dartmoor. I didn’t hold back. Among other things, I argued that our national parks should be reclassified as ecological disaster zones, pending a complete reassessment of the way they are managed. (You can watch the talk here, gallantly posted on YouTube by the Dartmoor National Park).

While the talk generated controversy, to my astonishment I found that many of the park staff at the conference appeared sympathetic to my arguments. There is, I discovered, a widespread sense that we cannot go on like this, that we cannot keep destroying in the name of protection. Something has gone badly wrong here, and there is an urgent need for change.

* P.Shaw and DBA Thompson, 2006. The nature of the Cairngorms: diversity in a changing environment. TSO: Edinburgh. 444 pp. ISBN: 9780114973261