What the governments of the Global North don’t care about, they don’t measure.

By George Monbiot, published in the Guardian 21st November 2025

I began by trying to discover whether or not a widespread belief was true. In doing so, I tripped across something even bigger: an index of the world’s indifference. I already knew that by burning fossil fuels, gorging on meat and dairy, and failing to make even simple changes, the rich world imposes a massive burden of disaster, displacement and death on people whose responsibility for the climate crisis is minimal. What I’ve now stumbled into is the vast black hole of our ignorance about these impacts.

What I wanted to discover was whether it’s true that nine times as many of the world’s people die of cold than of heat. The figure is often used by people who want to delay climate action: if we do nothing, some maintain, fewer will die. Of course, they gloss over all the other impacts of climate breakdown: the storms, floods, droughts, fires, crop failures, disease and sea level rise. But is this claim, at least, correct?

The figure comes from a study using the widest available datasets to try to produce a global view. The results are, to say the least, surprising. For example, it suggests that even in the hottest parts of the world, more people die of cold than from heat. In fact, sub-Saharan Africa appears to have the world’s highest rate of deaths from cold and the world’s lowest rate of deaths from heat. The figures suggest that 58 times as many people there die of cold than of heat. While it’s true that in hot places people are less adapted to cold, can this really be so?

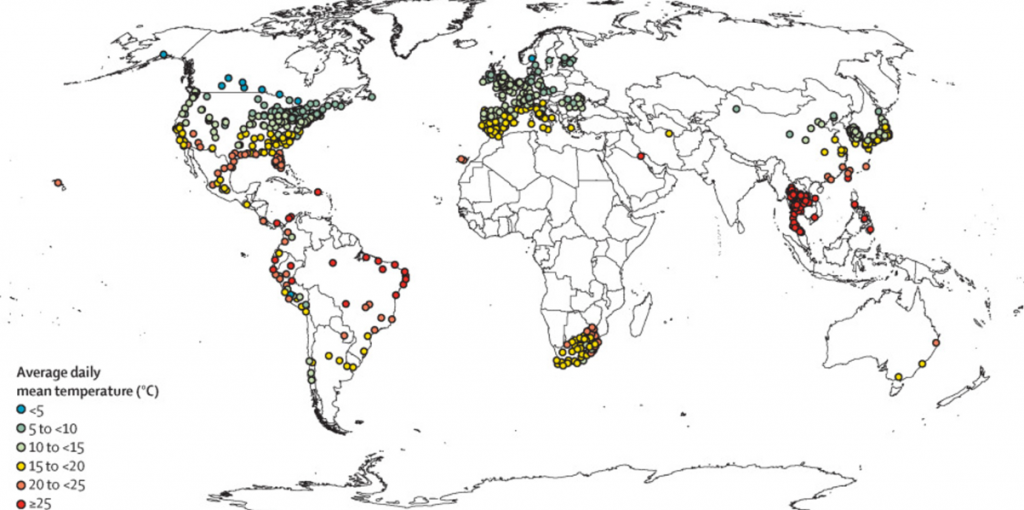

The paper explains that its dataset “covers 750 locations in 43 countries or territories”. But the only African country covered is South Africa. Nor are there any data from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, the Gulf states (except Kuwait), Iraq, Indonesia or Melanesia. In other words, most of the world’s hottest countries are not represented. Nor are most of the places in which healthcare is weakest, either for the population as a whole (as in some African nations) or for the most vulnerable people (as in the Gulf states, where citizens might be well covered, but migrant workers scarcely at all). This is in no way the fault of the authors – it’s simply a matter of where records are available.

A map of the global data we possess on temperature-related deaths.

From Zhao, Qi et al., 2021. Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study.The Lancet Planetary Health, Volume 5, Issue 7, e415 – e425

The study had to model global trends from places in which data exist, which tend to be richer, cooler countries, where health systems are relatively strong. There’s nothing I can see that’s wrong with the methodology: it’s just that the records are so patchy. As one of the authors, Prof Antonio Gasparrini, told me, their extrapolation “was moderate in some areas, but more extreme in others … in some cases the degree of extrapolation (especially geographical) was huge, and we cannot rule out that the model works less well in some regions”. They are currently trying to improve it. A subject that we, as the main agents of chaos, have a moral obligation to understand looks on the map like an enormous hole with a few ragged edges.

A paper published in 2020 points out that in large parts of Africa, there is no record even of extreme heat events, though they certainly happen. Heat events mean major temperature anomalies, in which large numbers of people could be expected to die. The crucial international disaster database EM-DAT records only two heatwaves in sub-Saharan Africa between 1900 and 2019. They were deemed to have caused the deaths of 71 people. The same database lists “83 heatwaves in Europe between 1980 and 2019, resulting in over 140,000 deaths”.

Even the extreme African heatwave of 1991-1992 was not reported in the EM-DAT database. Given that people in Africa tend, as the paper remarks, to have “higher levels of vulnerability and exposure” than people in Europe, is it really credible that fewer die of heat on that continent than on any other?

Far from the improvement in data we might expect, there has been a rapid and catastrophic decline in the number of weather stations measuring conditions across Africa. There are now blocks hundreds of miles wide in which not a single station is recorded. As the climate scientist Tufa Dinku points out: “Coverage tends to be worse in rural areas, exactly where livelihoods may be most vulnerable to climate variability and climate change.”

This is to say nothing of weather radar stations, which observe and forecast weather patterns and are essential for early warnings. In the US and Europe, where 1.1 billion people live, there are 565 of these radar stations, while in Africa, where 1.5 billion live, there are 33, according to the World Meteorological Association. Without weather warnings, many more people die.

As for heat deaths, the epidemiologist Prof Kristie Ebi points out that even in the US the official estimate, of about 1,200 a year, “is probably at least a tenfold undercount”. The great majority are recorded as heart attacks, kidney failure or other conditions. But epidemiological data show how deaths spike during heatwaves. Heaven knows how much underreporting there may be in countries with much sparser records.

The same applies to other impacts of global heating. A paper published in Nature last week revealed that the deaths caused by rainfall in Mumbai “are an order of magnitude larger than is documented by official statistics”. Most afflicted are slum residents, especially women and children. People, in other words, who are deemed not to count.

We could see the global underfunding of data collection as an index of how little powerful governments give a damn about human life. It reminds me of the statement the US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld made during the 2003 Iraq war, that came to stand for the Bush administration’s bloody insouciance: “We don’t do body counts on other people.”

How can vulnerable nations be compensated for the “loss and damage” caused by climate breakdown if we haven’t the faintest idea how great that loss and damage might be? So far, rich countries have pledged just $788.8m to the UN’s fund. That’s 44 US cents for each of the 1.8 billion citizens in the Climate Vulnerable Forum nations: the sum total of our “compensation” for the disruption, disaster and death we have caused.

The Cop30 summit could be represented as a vast shrug of rich-world indifference: we neither know nor care, so why should we confront our populations with the need for change, with all the political difficulty that involves? Turn your face from the void, for fear of the moral challenge it presents.